How We Research: A Look Inside the Buffer Blog Process

I often get asked about my research process for the Buffer blog. For my science and life hacking posts in particular, I rely heavily on scientific research to back up my points, so there’s a lot of research to be done.

Unfortunately there’s no secret sauce or magic bullet when it comes to this process. It’s mostly just a matter of time and practice. I do have a few tips to share about where and how I find the sources for my research, though, so hopefully you’ll find these useful.

Finding the research you need

The first thing I do when I start a research-heavy post is start digging into the topic to learn everything I can. Here are a few ways I find studies and research papers for my posts.

Google Alerts

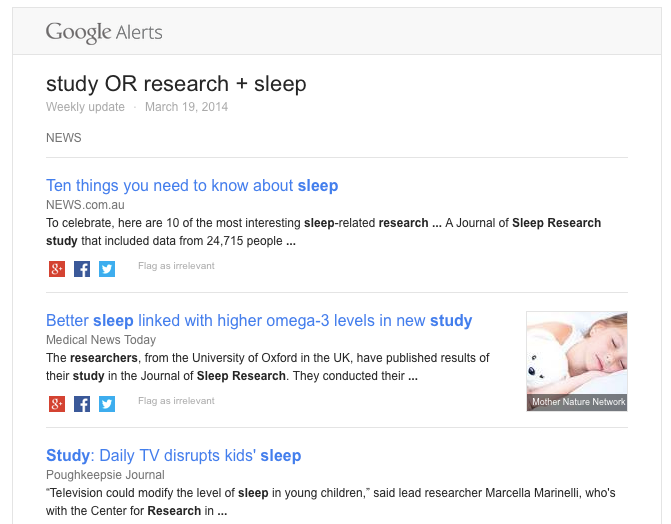

I have a few different Google Alerts set up to send me new research papers. Thanks to some advice from Leo, I usually get interesting scientific studies in my inbox once a week from these alerts.

Most of my alerts include the words “study OR research.” Using Google’s search operators like OR make my results more useful.

Here are some of the alerts I have running currently:

- study OR research + sleep

- harvard OR stanford OR columbia AND “new research”

- study OR research + exercise

Just head to google.com/alerts to set up a new alert, and choose to have it delivered immediately, daily or once per week. I get mine once per week so my inbox isn’t overloaded, and I usually run through the list and save any interesting links to my reading list.

Read a lot

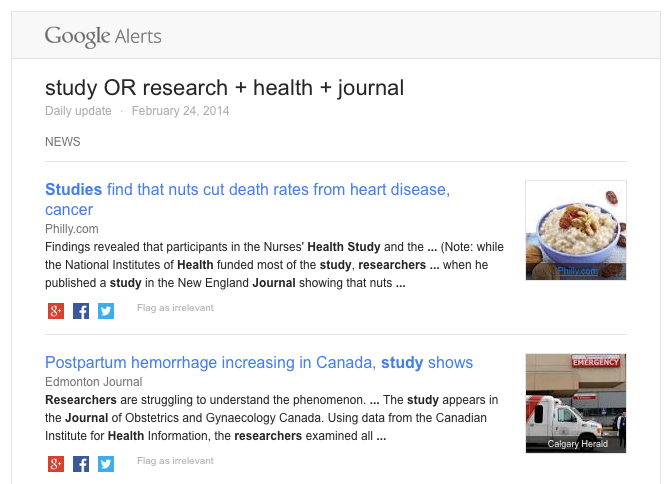

The other way I collect research material is to simply read a lot. I follow authors and blogs I like reading on Twitter—you might prefer to use RSS, Facebook or Google+ for this. Whenever I come across something that seems interesting, I save it to my read later list.

I end up reading a lot of material that I never use, because I always keep track of things that might be relevant some day, rather than only what I need right now. I try to keep track of ideas and topics I read about, however, so that I can come back to them later on when they are relevant.

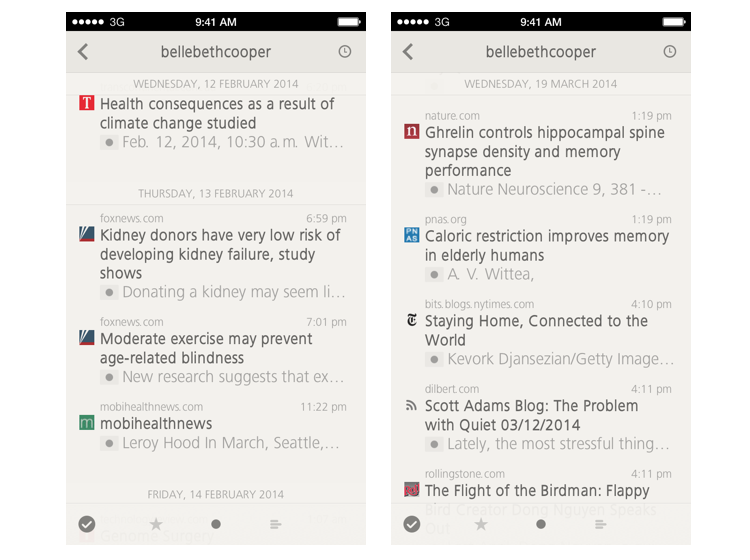

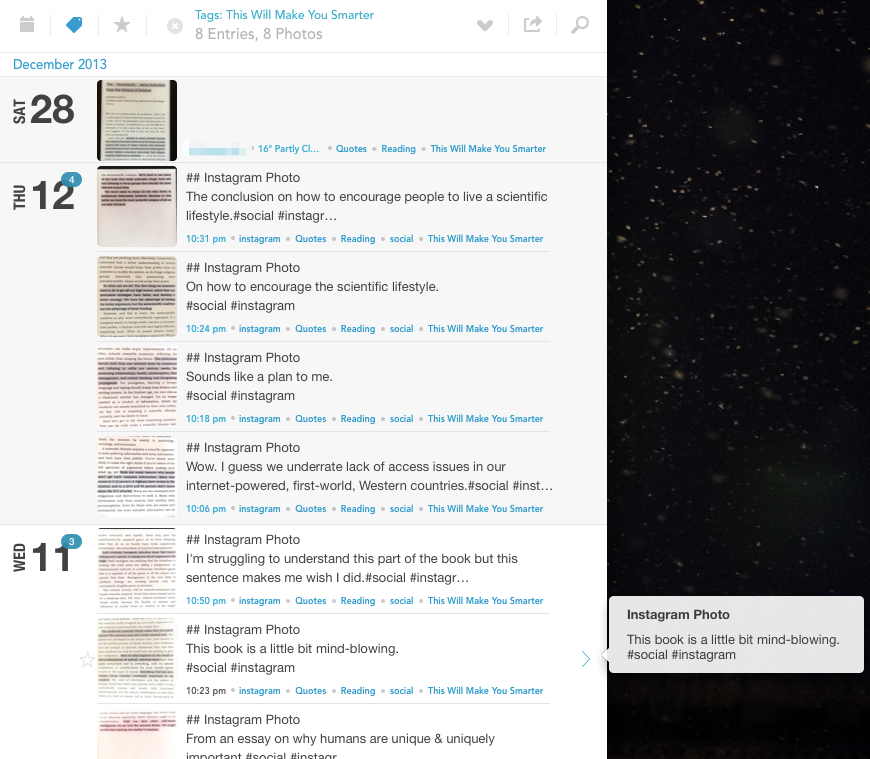

For instance, I use Day One to save quotes from blog posts or books I read, and tag them with whatever topics they touch on. This makes it easy to go back through all of my saved quotes to see what’s relevant to the blog post I’m writing today.

I also drop ideas and notes into Day One, and tag them with topics they relate to. I used to use a Moleskine notebook for the same purpose, but I like being able to search by tags in a digital journal.

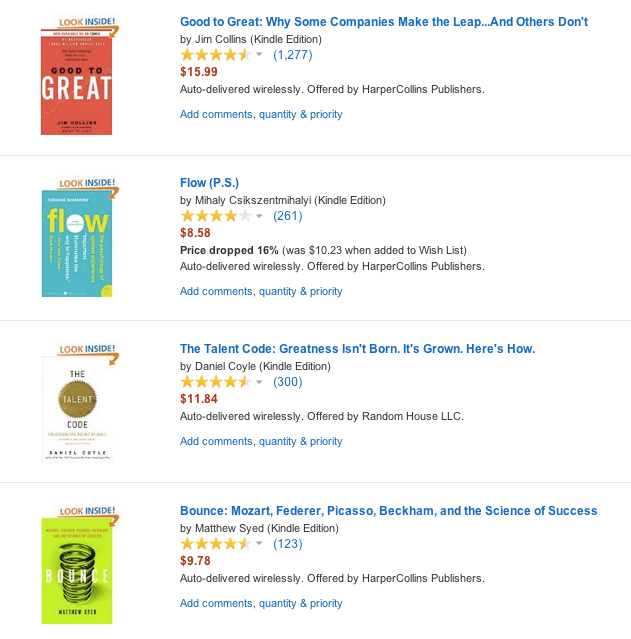

I also like reading related stuff, to expand my knowledge of particular areas. I often end up saving five or six books to my Amazon wishlist at a time, because I find a lot of the related books to be quite interesting. Here’s an example of what my wishlist tends to look like:

Bloggers often make this easy for you as well, by including links to related posts at the bottom of each one, or by including inline links to other, related posts they’ve written. Here’s an example of how we do this on the Buffer blog:

Save all the research you find

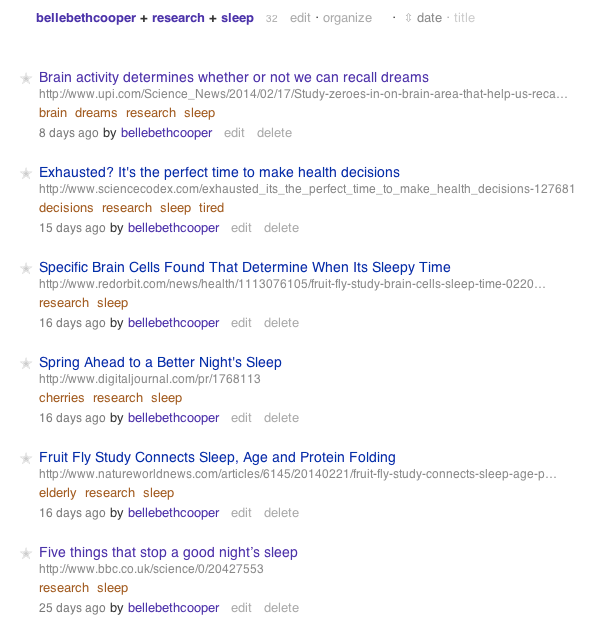

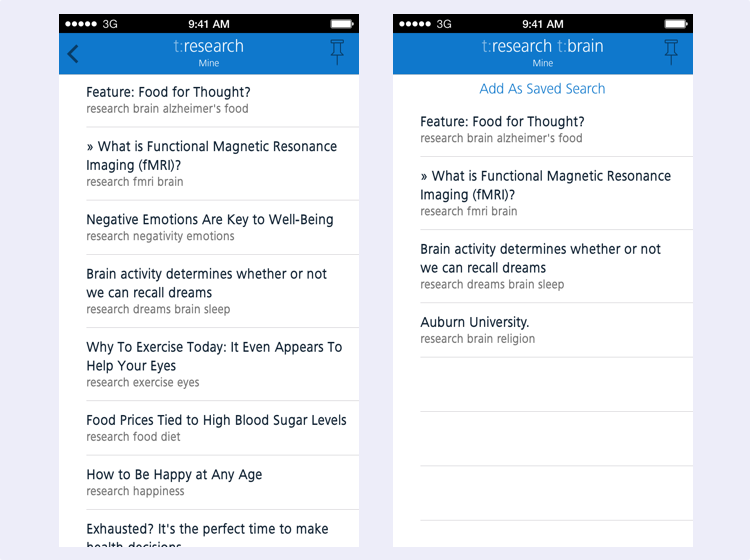

I save everything I read that might come in handy one day. I use Pinboard for this, but there are lots of free options you could try, such as Delicious, Kippt, Diigo or Saved.io.

I use multiple tags for each item. For studies, for instance, I’ll add the tag “research” and then tags like “sleep,” “naps” or “running” to help me find it again later.

Google searches

Once I have a good idea for a blog post I usually need a lot more research to fill it out. This is when I’ll turn to Google and start hunting for related studies. I usually start with a Google Scholar search:

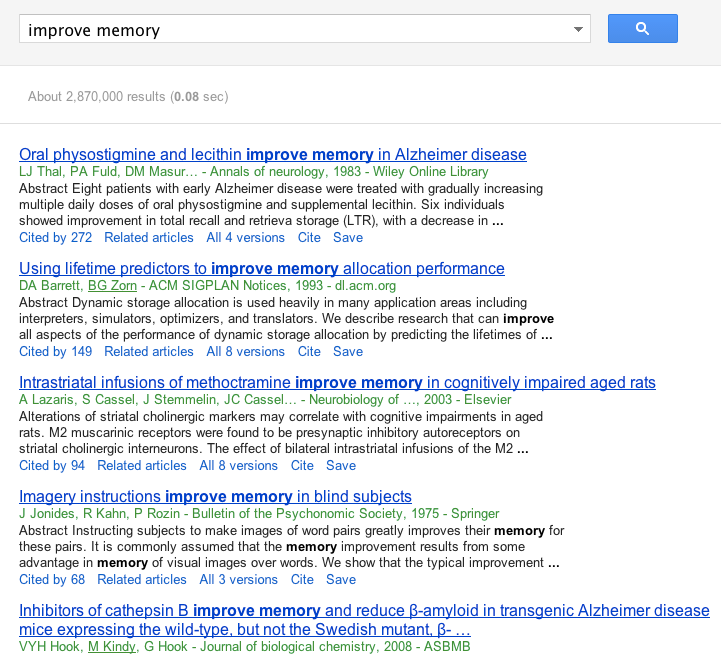

I usually start with a fairly basic phrase to start uncovering related studies:

After a few tries of different keyword combinations, I’ll start to work out which keywords researchers use in the kind of studies I’m after. This process isn’t usually much fun, but it’s important if I want to find the right studies for my topic.

The other useful thing about Google Scholar results is that they often show the number of citations a paper has received. This isn’t necessarily proof that it’s a high-quality paper, but it’s a clue that it’s at least popular and worth taking a look at. It’s a bit like when you see someone on Twitter with a high follower count: It doesn’t prove that they’re the best, but you’d probably give them a try, at least.

Bringing it all together

When I have some research ready for each point I want to make, it’s time to start bringing it all together into a draft.

Start with the basics

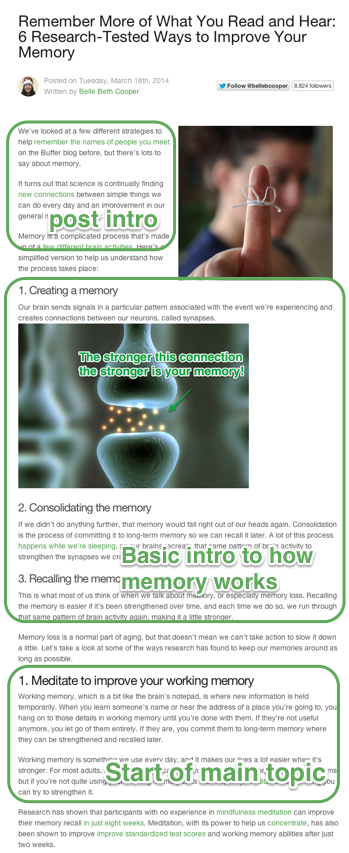

Usually I’ll find that I need some background about the basics of a topic I’m looking into—both for my own understanding and to add context for readers. A good example is this recent post I wrote: 6 Research-Tested Ways to Improve Your Memory.

I started out with a basic break down of how memory works before moving into the main topic of the post, which was how to improve your memory.

I get this basic information from a few places. One of my favorites is this book which covers each section and function of the brain in just a few pages. It’s a great way to get a really basic understanding of how something like memory works and where to start looking when I dive further into the research process.

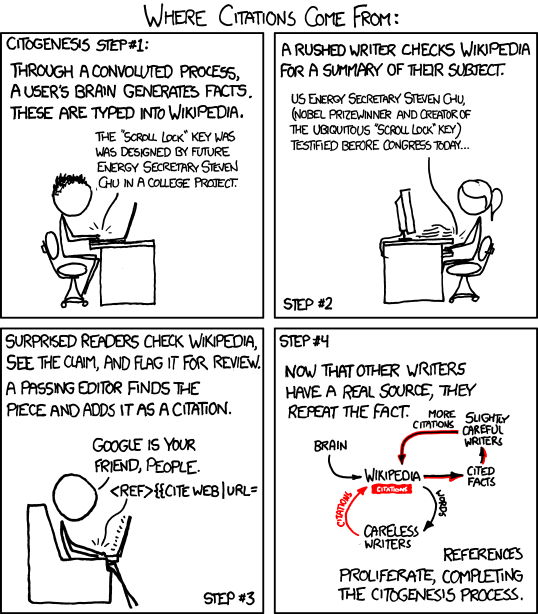

I also use Wikipedia for this. I don’t use Wikipedia as a research source, since it’s not reliable enough, but for my own understanding it’s a really helpful place to start.

Read studies carefully

From reading a lot of research studies, I’ve discovered a few important things that I try to keep in mind. Whenever I can, I read the full study rather than just an abstract. I usually find that any statistics and mathematics sections are beyond my understanding, but I find the introduction, results and discussion sections to be really helpful. The discussion section of a study paper usually talks about suggested causes of the results found, caveats to what the study has shown (such as a small sample size or results that apply to a specific group of people only), and related research areas.

Reading full studies can be quite expensive, so a lot of the time I’m stuck with only an abstract or a preview to go on. In these cases, I try not to draw conclusions from the abstract that may not be true—an abstract usually doesn’t include any caveats about the study, or a detailed analysis of what the results mean.

Link to original sources

Studies often get covered by multiple news sites which simplify the results of the research for a non-scientific audience. This can sometimes lead to inaccuracies and misunderstandings. For that reason, I try to always link back to an original study or source, rather than linking to someone who has interpreted the information. That’s almost like relying on other people to do your research for you.

Doing the work myself to fully understand the research I’m using helps me to feel more confident about backing up the points I make, and sharing information that isn’t misleading.

Don’t include everything

One of the most important things I’ve learned recently about research-heavy posts is that I don’t need to include every single bit of research I can find. A good example is this post I wrote about junk food cravings: Why we crave junk food and how to turn down the cravings.

I first got the idea for that post when I read about a study that showed eating avocado at lunchtime can stave off food cravings in the afternoon. Once I’d written the piece, I struggled to find a place to squeeze in that fact about avocados. No matter where I put it, it just didn’t fit in with the rest of the post. Eventually I realised it just wasn’t necessary.

Sometimes knowing what to cut is just as important as knowing what to write.

What research methods do you have? Let us know in the comments.

If you liked this post, you might also like From Ideas to Traffic Results: How We Run a Blog with 700,000 Readers Per Month and 6 Ways I’ve Improved My Writing In the Past 6 months You Can Try Today.

Image credits: El Bibliomata; xkcd

Try Buffer for free

180,000+ creators, small businesses, and marketers use Buffer to grow their audiences every month.

Related Articles

Stop chasing the tail-end of Instagram audio trends — here are the latest trending songs on Instagram in July 2025.

We pored over millions of posts on Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, TikTok, and LinkedIn to pinpoint when the best-performing content was published.

Learn how to leverage AI social media content creation tools and save valuable time in your social media marketing efforts.