You don’t have to be ‘the boss’ to take on a leadership role.

I learned that quite quickly while working with my startup—in many instances,

if you have the most experience within a certain skill, you’ll have to become the ‘leader’ during some key moments and guide the rest of the team.

What I happen to find fascinating is that numerous psychology studies tend to make a connection between this ability to lead when necessary and the achievement of professional success—especially for men.

The connection lead me to a question that guys have been asking themselves forever:

Do nice guys really finish last in life?

It’s hard to say for sure, but a new study shows that ‘nice guys’ typically earn less than their more aggressive peers.

Fortunately, the research doesn’t suggest that you need to be a jerk to get ahead in life, but that highly agreeable men need to be careful about how assertive they are when it comes their work. This assertiveness, as you’ll see, relates more closely to taking on the role of ‘leader’ than you might think.

Let’s take a look at why this phenomenon happens and what ‘nice guys’ can do about it.

The Problem with Nice Guys

According to a recent study by the University of Notre Dame, nice guys, at least statistically speaking, are not as likely earn the big bucks as their less agreeable peers.

The ladies are probably wondering, “What about us?”, but the study notes that this variable trait of ‘agreeableness’ only seems to detrimentally affect men:

The study shows a strong negative relationship between agreeableness and earnings for men. The more agreeable a man is, the less he will earn. For women, there is essentially no relationship at all.

Why?

Outside of the workplace, ‘Agreeableness’, one of the big 5 personality traits, is generally associated with positive characteristics, such as being warm, sympathetic, kind and cooperative.

It’s also the most commonly cited trait (of the big 5) when people describe an ideal person to spend time with, and most psychological research associates the trait with a slew of other positive behaviors.

So how do men benefit in the workplace by being the opposite?

According to the researchers, this double-standard exists because disagreeable men (at least in competitive, work-related scenarios) are viewed as tough negotiators and willing to stick to their vision, whereas women don’t gain the same benefit in terms of how they are viewed.

It seems that being ‘disagreeable’ isn’t really the ideal behavior, but rather that being too agreeable is viewed as a sign of weakness in men, or as a characteristic of a flaky personality that is lacking in confidence and conviction.

And yet, we’ve seen that being an agreeable person is a highly desirable trait in general, so how can a balance be found? Is there any correlation between assertiveness and other psychological traits that are associated with higher earnings and more work-related success?

I feel the answer lies in analyzing what makes a great leader, as leaders are quite likely to fill up high-earning positions, even if they aren’t ‘the boss.’

Examining leadership qualities also allows us to look past gender discrepancies, as leaders can be men or women and the traits are more universally applicable in the workplace.

So, what makes a great leader?

The Traits of Great Leaders

A lot has been written on being a great leader, but today we’ll take a look at two studies and their findings on what characteristics are

most important for those who wish to lead others.

The first comes in the form of some academic research on leadership qualities conducted by psychologists Robert Hogan and Robert Kaiser, and the second is a set of data from Jim Collins on what traits are most often associated with a great manager (a position regularly associated with leadership).

By examining the traits that have strong connections with leadership, we can see where ‘nice guys’ may be going wrong, and find out what it really takes to lead others and advance in a competitive environment that isn’t entirely accepting of overly agreeable people.

Let’s dig in…

1.) Decisiveness

The #1 trait across both sources, this characteristic is also the most at odds with being too agreeable.

When we watch others make decisions frequently and stick to those decisions, we subconsciously associate them with responsibility, and thus we are more likely to view them as leaders (especially when other people follow suite).

One study even found that first-movers often have the advantage in many decision making situations, as it only takes a few other people before the majority of the group will view the decision as valid. In essence, the person with the most conviction can create an availability cascade where others will agree with their opinions simply because they are presented so convincingly.

It’s easy to see why being too agreeable can hurt a man’s perceived qualities as a leader, as more agreeable men may look for a consensus to be formed first before they state their opinion, whereas more assertive men are likely to put their opinion forward immediately.

2.) Vision

A natural complement of decisiveness, as we know that a truly great leader does more than just shout his/her opinion the loudest—they back it up with a convincing explanation of how things are going to pan out.

Have you ever spoken with someone who was able to brilliantly articulate their idea to you one-on-one… but fell apart when they had to share it with a group? Sometimes this is the result of a fear of public speaking, and other times the person is just too agreeable to push for their vision in the face of opposing opinions.

In fact, research in the realm of creative thinking (often a fundamental aspect of leadership) has shown that brainstorming is often an ineffective method for coming up with ideas because participants can suffer from evaluation apprehension and social loafing, where they decide to rely on the rest of the group for ideas instead of putting forth their own. Most people are apprehensive about having their thoughts judged by others, which is why this occurrence is so common in group brainstorming sessions.

So skilled creative workers need to realize that what they plan out in their head doesn’t mean a thing unless they are willing to practice being able to present their idea persuasively (and confidently) to their peers and superiors.

3.) Persistence

While being persistent doesn’t necessarily mean being inflexible, there are certainly some differences between the stereotypical ‘agreeable’ personality and a persistent one.

One of the most interesting pieces of research I came across in this area is the denouncement of a tactic that I see many nice guys trying to use—playing devil’s advocate when they want to disagree.

Unfortunately, although being the devil’s advocate allows nice guys to keep pushing for their opinion without hurting any feelings, an insightful study conducted by Charles Namath shows that the tactic generally backfires—using a ‘devil’s advocate argument’ generally

strengthensthe group’s opinion on the original argument!

Conversely, true dissent was actually listened to much more closely and evaluated for much longer, as a majority of people will at least seek to understand the opposing argument of someone in the room before they dismiss it (that generally doesn’t happen when dealing with arguments between groups, but that’s for another day!).

Nice guys should therefore not only be persistent in their efforts towards greatness, but they also need to realize that ‘when to hold em’ and when to fold em’ applies to the workplace as well, and if they are confident in their stance/idea/argument, they need to push for it without trying to appeal to everyone.

The Case for Moderation

It should be noted that the other 3 big traits associated with great leaders (there were 6 in all) included things like Modesty, Competence, and Integrity, meaning it’s not always about conviction and confidence on the path to leadership.

That being said, before you close out this post and begin embracing some new Machiavellian lifestyle, you should know that the key trait we’ve thrown around, assertiveness, does have to be used in moderation.

What are the potentially negative impacts of being overly assertive?

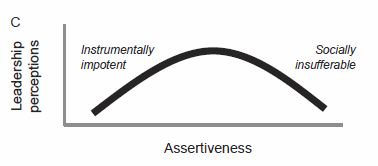

Research from Ames & Flynn (2007) sought to find that very answer. They gathered 3 groups of MBA students who were instructed to fill out questionnaires about their peers and the respective managers for whom they’d worked with in the past.

The main observations made examined social outcomes and instrumental outcomes—in other words, how well were the managers liked by the students and how much were they able to accomplish.

The results (as published on PsyBlog) were quite revealing:

- Productivity: higher and higher levels of assertiveness produced diminishing returns. So in terms of results it’s not much better to be highly assertive than moderately assertive, but it was definitely better to be moderately assertive than not assertive.

- Social outcomes: higher and higher levels of assertiveness lead to increasingly poor social outcomes. It was definitely better to be moderately assertive than highly assertive.

When you put both of the outcomes together you get an inverted U-shape (below; from Ames & Flynn, 2007). So that people who are low in assertiveness get less things done but people very high in assertiveness are socially insufferable.

In other words, forceful leadership doesn’t result in a rapid increase in productivity and can make the person in charge socially insufferable, a bad trait for long term leadership.

There seems to be a “sweet spot” where a leader’s presence is felt and their guidance listened to, but without the overbearing presence that tends to be detrimental to others in the group.

A leader is best when people barely know he exists, when his work is done, his aim fulfilled, they will say: we did it ourselves.

— Lao Tzu

It’s the seamless integration into the group with the clear understanding that one person is taking charge that creates an effective chemistry and allows for a great leader to thrive.

This is one instance where a photo from the web speaks a thousand words:

Your Turn

Now I want to hear from you…

What did you think of this research?- Have you had a great manager/leader in your professional life? What made you willing to follow them and heed their advice?

I’m interested in hearing that you think, so I’ll see you down in the comments!

About the Author: Gregory Ciotti is a content marketing manager at Help Scout, the invisible Desk.com alternative built for

providing exceptional email support for startups and small businesses.

Try Buffer for free

190,000+ creators, small businesses, and marketers use Buffer to grow their audiences every month.