Understanding the psychology behind the way we tick might help us to tick even better.

Many studies and much research has been invested into the how and why behind our everyday actions and interactions. The results are revealing. If you are looking for a way to supercharge your personal development, understanding the psychology behind our actions is an essential first step.

Fortunately, knowing is half the battle. When you realize all the many ways in which our minds create perceptions, weigh decisions, and subconsciously operate, you can see the psychological advantages start to take shape. It’s like a backstage pass to the way we work, and being backstage, you have an even greater understanding of what it takes to succeed.

The following 6 psychology facts can be viewed as a hacker’s guide to self-improvement, based on the brain’s default settings. So, that’s exactly what this is – your backstage pass to how our brain functions and how we can best avoid common misconceptions.

The Pratfall Effect – Your likability will increase if you aren’t perfect.

Don’t worry about tripping and falling in front of your boyfriend; doing so will only make him like you more. Go ahead and admit your failures to your friends; your humanness will endear yourself to them.

These mistakes attract charm as a result of the Pratfall Effect: Those who never make mistakes are perceived as less likeable than those who commit the occasional faux pas. Messing up draws people closer to you, makes you more human. Perfection creates distance and an unattractive air of invincibility. Those of us with flaws win out every time.

This theory was tested by psychologist Elliot Aronson. In his test, he asked participants to listen to recordings of people answering a quiz. Select recordings included the sound of the person knocking over a cup of coffee. When participants were asked to rate the quizzers on likability, the coffee-spill group came out on top.

Key Takeaway

The Pratfall Effect serves as a good reminder that it is okay to be fallible. Occasional mistakes are not only acceptable, they may turn out to be beneficial. So long as the mistakes are not critical and making mistakes does not compound a reputation for being unliked, the occasional pratfall can come in very handy. Pratfall away.

The Pygmalion Effect – Greater expectations drive greater performance.

The crux of this psychological phenomenon is the concept of self-fulfilling prophecy: If you believe something is true of yourself, eventually it will be.

The first test of the Pygmalion Effect was performed by psychologist Robert Rosenthal and occurred in an elementary school classroom with first and second grade students. At the beginning of the year, all the students took an assessment test, and Rosenthal led the teachers to believe that certain students were capable of great academic achievement. Rosenthal chose these students at random, regardless of the actual results of the IQ tests.

At the end of the year, when the students were retested, the group of earmarked high achievers did indeed show improvement over their peers. Why was this? Later tests concluded that teachers subconsciously gave greater opportunities, attention, and feedback to the special group. Their expectations for this group were higher, and their expectations created the reality.

Rosenthal summarized his finding:

What one person expects of another can come to serve as a self-fulfilling prophecy.

The effect was dubbed “Pygmalion,” named after the Ovid tale of a sculptor who falls in love with one of his statues.

Key Takeaway

The applications for the Pygmalion Effect can have benefits for both personal development and leadership. Individually, you can challenge yourself with more difficult goals and tasks in an effort to rise to meet the challenge. As a leader, when you expect great things of your team, you may see improved performance in return.

The Paradox of Choice – The more choices we have, the less likely we are to be content with our decision.

Have you felt buyer’s remorse? If so, you’ve seen the Paradox of Choice in effect.

Even if our ultimate decision is clearly correct, when faced with many choices, we are less likely to be happy with what we choose. No doubt this is familiar to you. When I eat out, I often second-guess my menu choice. When you buy a new car, you might toss and turn over the decision. A wealth of choices makes finding contentment that much harder.

To prove this paradox, psychologists Mark Lepper and Sheena Iyengar conducted an experiment on supermarket jam. At a gourmet food store, Lepper and Iyengar set up a display of high-quality jams and taste samples. In one test, they offered six varieties; another test, they offered 24. The results of the study showed that 30 percent of people exposed to the smaller selection ended up purchasing a jar of jam. Only 3 percent of the people exposed to the larger selection purchased jam.

The fame of the jam study coupled with a popular book and TED talk by psychologist Barry Schwartz make the paradox of choice one of the most publicized (and criticized) psychological phenomenons. Perhaps the best affirmations of this tyranny of choice are its common sense explanations: Happiness is diminished with the extra effort and stress it takes to weigh multiple options, opportunity cost affects the way we value items, pressure to choose can be draining, and the possibility of blame exists should the decision not turn out how we had hoped.

Key takeaway

A simple solution to the paradox of choice: Give yourself fewer options. A key to this is identified in the following excerpt from Schwartz’s book:

Focus on what makes you happy, and do what gives meaning to your life

The Bystander Effect – The more people who see someone in need, the less likely that person is to receive help.

The parable of the Good Samaritan illustrates this effect clearly. So too do many tragic events throughout history. Researchers call it a “confusion of responsibility,” where individuals feel less responsibility for the outcome of an event when others are around. In fact, the probability of help is inversely related to the number of people present. If you are to ever need assistance, don’t go looking for it in a crowd.

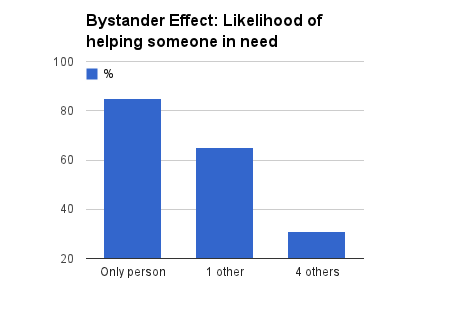

The Bystander Effect was shown in a study by social psychologists Bibb Latane and John Darley. They watched students respond to the perceived choking of a fellow student in a nearby cubicle. When the test subjects felt they were the only other person there, 85 percent rushed to help. When the student felt there was one other person, 65 percent helped. When the student felt there were four other people, the percentage dropped to 31 percent.

You may have experienced the Bystander Effect in a group project at school. There is often one group member who puts off deadlines and assignments because of diffused responsibility: They assume someone else will pick up the slack.

Key takeaway

Be specific when you need help. Ask someone for help by name so as to remove the confusion of responsibility. This is especially counterintuitive since we naturally assume saying to a larger group to help us will encourage more people to jump in, when really the opposite is the case. To avoid frustration, pick out 1 person only every time.

The Spotlight Effect – Your mistakes are not noticed as much as you think

The perception of our being under constant scrutiny is merely in our minds, and the paranoia and self-doubt that we feel each time we make a mistake does not truly reflect reality. According to the Spotlight Effect, people aren’t paying attention at our moments of failure nearly as much as we think.

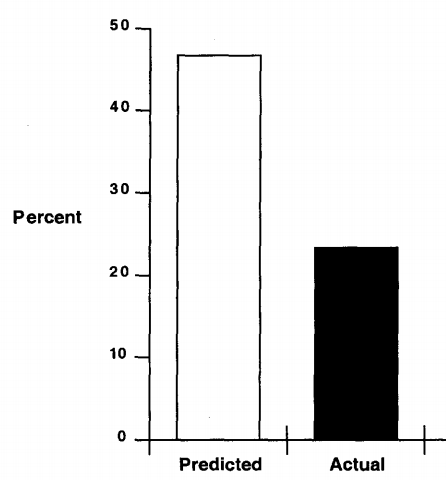

To test the Spotlight Effect, a team of psychologists at Cornell asked a group of test subjects to wear an embarrassing T-shirt (featuring a picture of Barry Manilow’s face) and estimate how many other people had noticed what they were wearing. The estimations of the test subjects were twice as high as the actual number.

Key takeaway

You are under the spotlight less often than you think. Acknowledging this should lead to increased comfortability and relaxation in public settings and more freedom to be yourself. More so, when you do make a mistake, you can rest easy knowing that its impact is far less than you think. Psychologist Kenneth Savitsky puts it this way:

You can’t completely eliminate the embarrassment you feel when you commit a faux pas, but it helps to know how much you’re exaggerating its impact.

The Focusing Effect – People place too much importance on one aspect of an event and fail to recognize other factors

“Nothing In Life Is As Important As You Think It Is, While You Are Thinking About It” – Daniel Kahneman

How great is the difference in mood between someone who earns high income and someone who earns lower income? The difference does exist, but it is one-third less significant than most people expect. This illustrates the Focusing Effect; in the income example, the factor of income as it relates to mood overshadows the myriad other circumstances at play.

How much happier is a Californian than a Midwesterner? When psychologists posed this question to residents of both areas, the answer from each group was that Californians must be considerably happier. The truth was that there was no difference between the actual happiness rating of Californians and Midwesterners. Respondents were focusing on the sunny weather in California and the easy-going lifestyle as the predominant factors in happiness when in fact there are many other, less publicized aspects of happiness that Midwesterners enjoy: low crime, safety from earthquakes, etc.

Marketers use Focusing Effect (also called focusing illusion) on consumers by convincing them of the necessary features of a product or service. Politicians, too, use focusing to exaggerate the importance of particular issues.

Key takeaway

To combat this effect, it is important to remember to keep perspective, look at problems from many angles, and weigh several factors before making a decision. The downfall of the Focusing Effect is that it can lead to mistakes in predicting future outcomes. If you can avoid tunnel vision (or at least acknowledge that it may exist), you can improve your chances of making a sound choice.

Over to you now. Have you ever experienced some of these psychological effects before? If so, how did you deal with overcoming them? I’d love to hear your thoughts on the topic and see what the best ways are to combat them.

P.S. If you liked this post, you might enjoy our Buffer Blog newsletter. Receive each new post delivered right to your inbox, plus our can’t-miss weekly email of the Internet’s best reads. Sign up here.

Try Buffer for free

190,000+ creators, small businesses, and marketers use Buffer to grow their audiences every month.