“A large state does not behave at all like a gigantic municipality” – Nassim Nicholas Taleb

What does this statement make you think? Disagree at all? When I first read that line, I thought “Oh really? Here are some reasons why a large state could in fact behave like a gigantic municipality...” I was inclined to find fault with the statement even if there is some merit.

But it’s not the author’s fault: persuasion is hard. Here are some of the most fascinating studies, that if we just glance at them, make us believe that we almost don’t trust anyone:

Studies have shown how little people generally trust strangers. Surprisingly, studies have even shown that people trust loved ones even less than strangers, suggesting that even familiarity doesn’t compel us to trust people or believe what they say. Furthermore, the fact that people are subject to the false-consensus bias – we tend to believe that people agree with us when they do not – obscures when we need to be persuasive.

This exacerbates the divide between stakeholders with different perspectives. It also makes it harder to persuade people because we may not realize that they even need to be persuaded. Let’s take this example from a recent study at Yale:

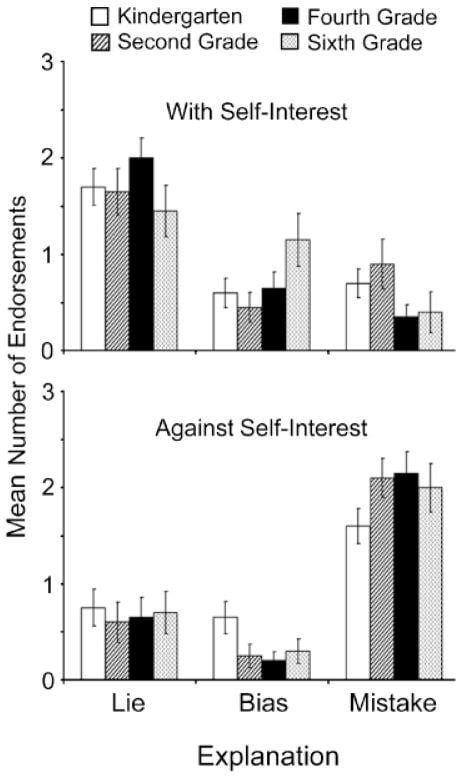

If something is against your self-interest, it rarely matters whether it is true or false, you are much more likely to be mistaken with your choice. This is a graph about the likelihood of schoolchildren making a mistake if it’s in their self-interest or if it isn’t:

Thus, credibility, data, and familiarity are not the only, or most effective, tools for persuasion. After all, the above claim about large states and gigantic municipalities, is part of a renowned book from acclaimed author Nassim Taleb. It is a fairly logical claim, and the source is credible. Yet I still had my skepticism about its validity.

So, let’s rephrase Nassim Taleb’s statement from above:

“A large state does not behave at all like a gigantic municipality, much as a baby human does not resemble a smaller adult.” – Nassim Nicholas Taleb

“Wow. You’re right, Nassim. Babies are not simply smaller adults. I guess large states really are not like gigantic municipalities” is what I thought to myself. Indeed, this was the actual statement used in his book. It is far more persuasive.

By asserting an obvious, uncontroversial statement and drawing a comparison to the more controversial assertion, you can get your listener to assign the same belief they have in the uncontroversial statement to the more controversial assertion. While I have my doubts about the first relationship Taleb posited – between states and municipalities – Taleb got me to quickly nod along with his argument by using the power of analogy and drawing a comparison.

I agreed with the second relationship he posited regarding babies and small adults and how they are not the same. There is a fundamental difference between babies and adults beyond physical size. Importantly, Taleb also managed to get my assent to the more controversial statement by making a logical leap through his comparison: Baby Human : Smaller Adult = Large State : Gigantic Municipality.

Why Drawing Comparisons with Analogies and Metaphors are key to Persuasion

By claiming that the first relationship is effectively the same as the second, doubts about how a large state does not behave at all like a gigantic municipality just faded away. Robert Cialdini, a professor and author of the best-selling Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion has brilliantly documented how uncovering real similarities can be fundamental to forging bonds – often between people – but also between ideas in the course of debate or conversation.

Analogies, similes, and metaphors are tools to surface similarities and draw comparisons. Thus, these can be very powerful tools for persuasion.

But what is it exactly about drawing comparisons that can turn questionable assertions into believable statements? Effective comparisons are simple, distracting, and depersonalized, and these characteristics help make assertions believable and people persuasive.

Simplicity Provides Meaning To Your Audience

“…a baby human does not resemble a smaller adult” is a simple idea. Think baby. Think short or skinny adult. Babies and adults are fundamentally different in many ways – emotional maturity, mental complexity, and so on.

The idea that a baby does not resemble a smaller adult is easy to understand. However, states and municipalities are complex, intellectual concepts that each raise lots of questions for people. This complexity makes it hard to achieve agreement – not because the statement is necessarily controversial, but because it is complicated and people may not feel like they understand the relationship.

By taking a very complicated idea that may make someone raise an eyebrow, and framing it in a much simpler context, you can give people a better understanding of the point you are making. When people understand your argument, it helps reduce skepticism borne from the unknown. It is almost as if one simply takes the simplicity from the latter idea and applies it to the more complicated idea.

Shift the focus away from the point you want to get across – the famous Gorilla Test

Had the sentence only been “A large state does not behave at all like a gigantic municipality” one would be fixated squarely on just that argument. However, it begins there, but finishes by comparing babies and adults, which shifts the focus away from states and municipalities onto the simpler comparison.

By diverting people from the complicated, nuanced argument that is initially put forth with a simpler ending, the author shifted scrutiny away from the most controversial part of the statement. In doing so, people are not focusing their energy on picking apart states and municipalities, which lowers the barriers to getting buy-in, but instead are thinking about babies and adults.

Credit: Daniel J. Simons, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vJG698U2Mvo

In this famous selective attention test, the audience is instructed to focus on how many times the basketball is passed among players wearing white t-shirts. Many people miss the “invisible gorilla” that passes through because their attention was diverted by a specific task.

Try to depersonalize: It reduces uncertainty and emotional resistance

People can get defensive about change for reasons like loss of control or loss of face (i.e. they look bad). When persuading people, it is hard for it to not be personal: you are changing their world view. In doing so, if people feel attacked, inferior, or wrong, it naturally sparks a desire to resist that change or assertion.

By drawing a comparison to a neutral subject, like babies and adults, the author reduces the likelihood that you will have a negative, visceral reaction to his statement. Imagine instead if the author suggested that the large states and gigantic municipalities share the same relationship as your family and your neighborhood, and that a large version of your family is not simply the same as a big neighborhood.

The characters in The Godfather are notorious for claiming to not take things personally. It clouded judgment.

Now one must be thinking “Well, my family is…[insert a slew of personal details]”. Not only does making the comparison personal introduce a lot of uncertainty (How can the author know what each reader’s family life is like?), but that uncertainty and the reality of one’s family life may invalidate his comparison. Perhaps that person’s family would indeed represent a neighborhood if it were much larger, and now one has made a claim that contradicts the reader’s own beliefs about their family.

The uncertainty and emotional resistance that comes out of making statements personal, especially when one doesn’t know the personal reality for each audience member, makes it very difficult to be successfully persuasive. Depersonalizing the assertion strips the emotion out of the argument and reduces the likelihood of putting someone on guard.

Persuasion in Practice

Imagine the argument when Founder A wants to build a feature for a technology product and Founder B disagrees.

Founder A: “We should build infinite scroll. It’s going to be a winner.”

Founder B: “No, I disagree. Neither of us has the data, but I think you’re wrong. Listen to me.”

This simply boils down into one person’s subjective outlook against another’s. It is not simple because both arguments have obscured rationale. Founder B does not create a diversion with Founder A through a relevant comparison. And Founder B makes it less likely that Founder A will agree by making the argument extremely personal.

But, what if Founder B compares this moment to a relevant shared experience, and draws comparisons between this moment and a previous moment both founders experienced together.

Founder A: “We should build infinite scroll. It’s going to be a winner.”

Founder B: “No, I disagree. This is just like that time when we tried building our own relational database. We wasted 3 months of work.”

It’s simple to recall a previous experience that was painful. It creates a diversion from the current feature by focusing on a precedent. And it’s not about Founder A being wrong – it’s depersonalized and about the resources that the team cannot afford to waste.

“Wow. Building that database really costs us a lot. I don’t want to face down that beast again” may be what Founder A now thinks. The comparison is simple, diverting, and depersonalized.

To be fair, a discerning person would of course question the comparison – is infinite scroll really like building your own relational database? Are the risks the same? Perhaps not. But it would require a willingness to disagree and an ability to call someone out to defend against what is otherwise effective persuasion.

A person is listening to you, digesting what you say, and even if they disagree about the precision of your argument…you have now put them in a lens of thinking about the comparison you have made, not its fundamental, independent validity.

How have you drawn comparisons to win people over and persuade? Let us know in the comments below, we’d love to hear your thoughts.

About the author:

Jason Shah is a product manager at Yammer and the creator of HeatData, an analytics tool that shows you where people tap, swipe, zoom, and more on your mobile websites and apps.

He blogs about user experience and personal growth at blog.jasonshah.org, and you can follow him on Twitter @jasonyogeshshah.

Photocredit: Digitallifeplus, Costumeshopper

Try Buffer for free

190,000+ creators, small businesses, and marketers use Buffer to grow their audiences every month.