I was reading an excellent book recently when I came across the concept of the “Big Five” personality traits. I’d never heard of these before but I found them fascinating. You’ve probably taken personality tests in the past—the Meyers-Briggs test is a popular one. The Big Five are more often used in scientific circles for personality research, so I think they’re handy to know.

I also enjoyed reading about the implications these could have for managers or anyone in charge of groups of people (teachers, sports coaches, even parents).

I’m fairly confident everyone can benefit from understanding how the Big Five work and paying attention to the personality traits of ourselves and those around us, so I’d like to share what I’ve read about the Big Five and some suggestions for using them to your advantage.

What are the Big Five

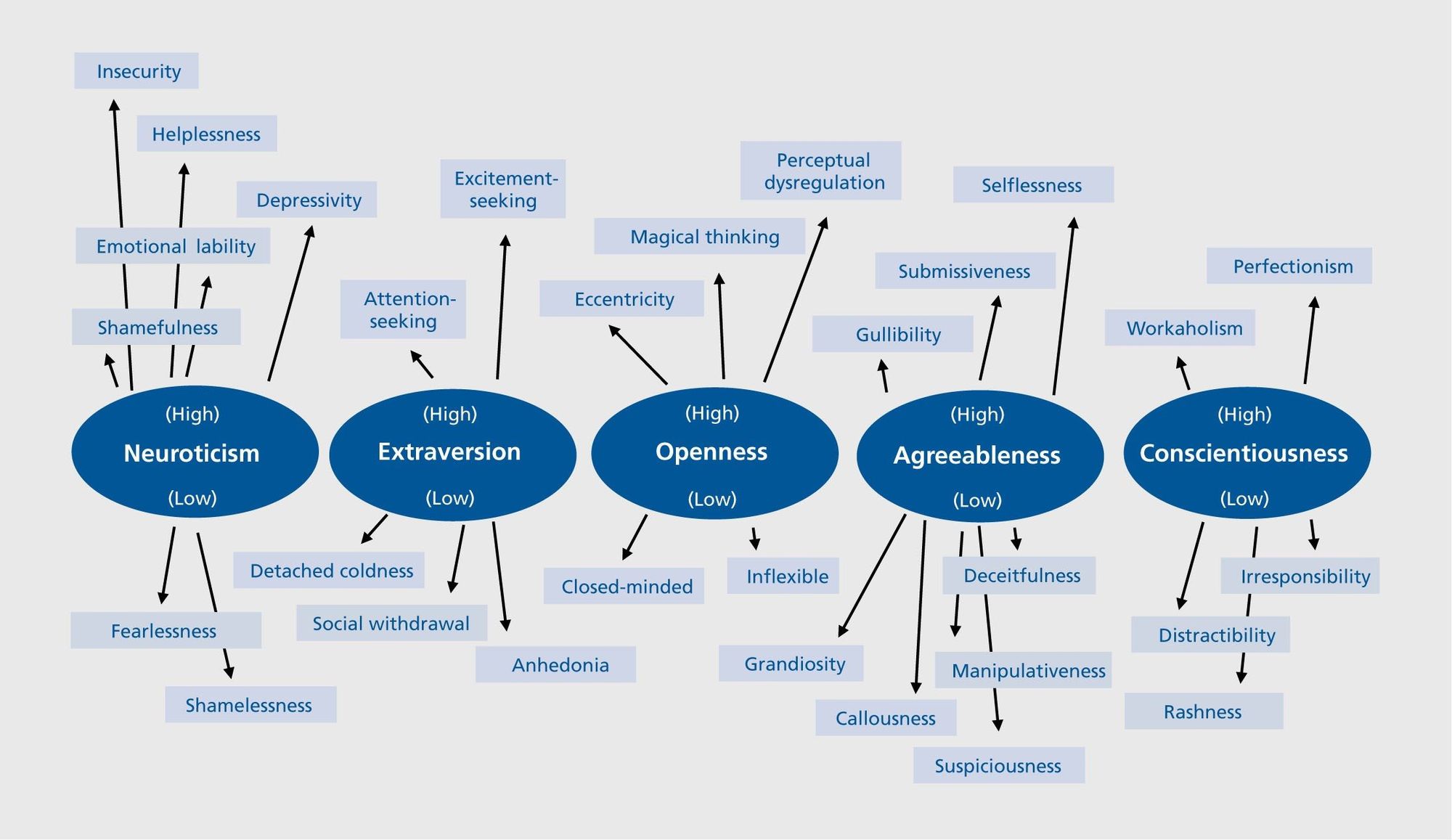

In the 1970s, two groups of personality researchers independently came to the conclusion that most personality traits can be boiled down into five broad categories, now known as the Big Five. They are:

- Openness

- Conscientiousness

- Extraversion

- Agreeableness

- Emotional stability (or Neuroticism)

I first read about these in an essay by Geoffrey Miller in the book I mentioned earlier. He explained that each of these traits acts like a scale, where everyone falls at some points along the scale between high and low. I’ve actually written about the scale of extraversion and introversion before, but I didn’t realize at the time that it was part of the Big Five lineup.

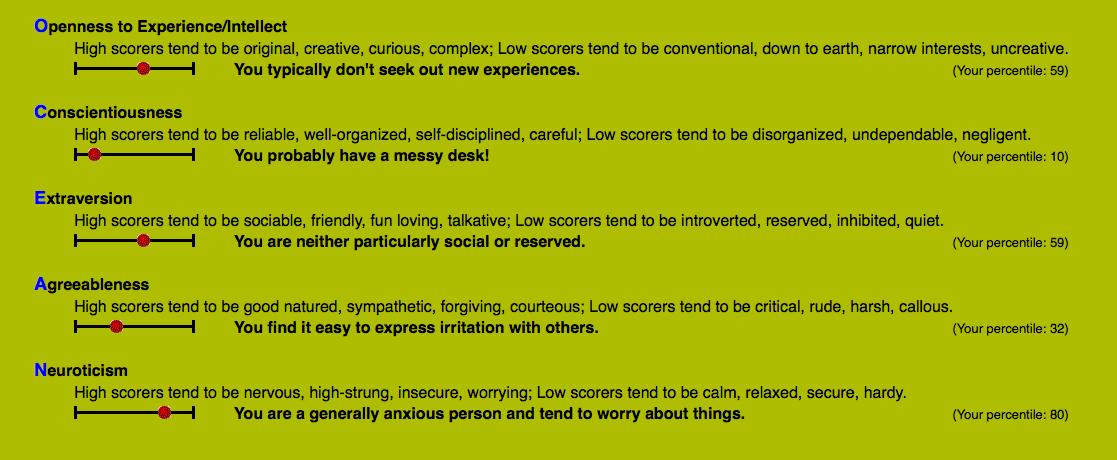

If you’re curious about these, you can try this online test to see how you score. Here’s what my results looked like (though I’m not so sure I believe this is me!):

Another essay in the same book, by Helen Fisher, explored “Temperament dimensions,” which are very similar broad categories to those above, excluding extraversion. One important note to make about both of these models of describing personality traits is that they are very broad, general categories. They came from patterns that emerged from large amounts of research data, so they can’t pinpoint your exact personality. They can be used as a helpful guide, but not a hard-and-fast rule set.

Let’s explore how each trait presents itself in our personalities:

Openness: Those who score high for this trait tend to enjoy adventure and be open to new experiences

Conscientiousness: High scorers for conscientiousness are generally organized and dependable

Extraversion: Those who are high on this scale draw their energy from being around others, so they tend to be more sociable (not to be confused with outgoing!)—read more about this trait in my previous post.

Agreeableness: High scorers for this trait are often trusting, helpful and compassionate.

Emotional stability: People with high scores for this trait are usually confident and don’t tend to worry often (this may be tested as neuroticism, in which case high scorers would be prone to worrying and anxiety).

Geoffrey Miller’s essay emphasized how each of these works as a scale, or really a bell curve, with all of us falling into the range somewhere. I loved this point he made, which really put things into perspective for me:

One implication is that the “insane” are often just a bit more extreme in their personalities than whatever promotes success or contentment in modern societies—or more extreme than we’re comfortable with.

Although these traits are genetically heritable and mostly stable throughout our lives, Helen Fisher’s essay emphasized the fact that people are malleable:

We are not puppets on a string of DNA.

Thus, if you tend to score high on a trait you’re not especially keen on, you can work on this. It takes work, though. Helen also made the point that while we are capable of acting “out of character,” this is exhausting and we can’t keep it up for long. Small increments are generally best to create lasting change.

Now that we understand what the Big Five are and how they present in people, let’s take a look at why this information is useful to us.

Again, Helen Fisher has an excellent point to make on this:

… we are social creatures, and a deeper understanding of who we (and others) are can provide a valuable tool for understanding, pleasing, cajoling, reprimanding, rewarding, and loving others.

I couldn’t agree more. In particular, I think this information can help us to understand and help our employees even better.

Building a better team using personality traits

Whether you’re looking for a way to build a more cohesive team with the people you already manage or you’re hiring, like Buffer, you can put these personality traits to work if you understand them well.

1. Take note of the personality traits you need before hiring

Before you hire for a new role, you’ll probably put together a job description. This helps you to understand what kind of person you’re looking for: what skills and experience they’ll have, and what they’ll be able to bring to your company.

Using the Big Five, you can put together a rough blueprint of the personalities you already have in your team and make a note of which personality traits would best fit into the new role.

2. Look for personalities that will fit into and compliment your company culture

We’re big on culture at Buffer, and this is something I think we could add into our hiring process to make even better decisions about who will fit in best.

Understanding the personality traits that suit the role you’re hiring for is important, but how personalities fit together can make a big difference as well. Working out the personality traits most suited to your company’s culture can help you to keep an eye out for them and spot people who will fit in more easily.

3. Pair new employees up with team members who suit their personality type

When new employees come on board it’s fairly standard for an existing employee to show them the ropes. If you’re buddying up new employees for a while, taking personality types into consideration could make your employee on boarding process smoother.

Do you have any other suggestions for using personality types in hiring or bringing your team together? Let us know in the comments.

P.S. If you liked this post, you might also like Why positive encouragement works better than criticism, according to science and 22 Tips To Better Care for Introverts and Extroverts.

Image credit: Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience

Try Buffer for free

190,000+ creators, small businesses, and marketers use Buffer to grow their audiences every month.