Twitter hashtags are so ingrained in Twitter now that I rarely second-guess them. They seem so much a part of the service, it’s as if Twitter shipped with them in its original version, even before it had vowels in the name.

But actually, Twitter’s version of the hashtag has a vibrant history which is really fascinating. Let’s take a look at the origins of the hashtag and how to use it best on Twitter.

The origin of the hashtag

The very ephemerality of hashtags is what makes them easy and compelling to use in a fast-moving communication medium like Twitter. – Chris Messina

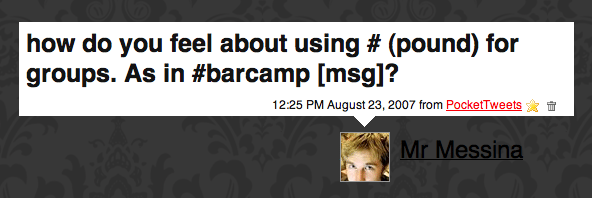

The hashtag was first brought to Twitter on August 23, 2007 by Chris Messina. Before this, the hash (or pound) symbol had been used in various ways around the web, which helped Chris in developing his detailed suggestion for using hashtags on Twitter.

Chris took direction from similar uses of the hash symbol he’d already seen on other sites when designing the hashtag for Twitter.

It occurred to me that IRC presents a proven model for these needs with its foundation on channels, and so that’s what I’m generally going to call them.

Chris also wanted to find a way to incorporate hashtags into his current use of Twitter, so that SMS or IM clients could be used to interact with hashtags, and no web-based management would be required to set them up. He looked to a similar social network, Jaiku for a good example:

Jaiku comes closest with their channels implementation, making it extremely easy to create new channels (simply post a message that begins with a hash (#) and your intended channel name — and if the channel doesn’t exist, it’ll be created for you).

Chris also looked to Flickr tags for inspiration when he tried to increase adoption of his new hashtag convention on Twitter.

During the Californian wildfires in October 2007, Chris chose the popular Flickr tag “sandiegofire” and encouraged others to use it to group their tweets by topic.

Bringing the hashtag to Twitter

In Twitter’s early days, many people were keen to see some kind of “groups” feature. A good example is this early discussion on Get Satisfaction, which begins with a plea for a grouping-type feature:

I would love to be able to send certain messages only to certain sets of people through some sort of grouping functionality.

Like when I go to a conference, I want to be able to send certain messages only to other twitter friends who are also at that conference. A lot of my friends get really annoyed with me when I’m constantly twittering about an event they’re not lucky enough to attend.

Chris wasn’t convinced that groups were the way to go, but rather wanted to improve “contextualization, content filtering and exploratory serendipity”:

I’m more interested in simply having a better eavesdropping experience on Twitter.

After thinking through how hashtags could work on Twitter, Chris wrote a blog post to share his ideas. The post outlined some of the hashtag features we know well today as well as some that didn’t make it to the platform (or at least didn’t last, anyway). For instance, the “folksonomic approach”—that is, we can create and leave behind hashtags on an ad-hoc basis:

I imagine that #barcamp will be a common tag between events, but that’s fine, since if there is a collision, say between two separate BarCamps on the same day, they’ll just have to socially engineer a solution and probably pick a new tag, like #barcampblock

This is something we see happen even today, as hashtags are created and dropped on-the-fly. Another thing Chris planned for was reusing hashtags, which can come in handy for annual conferences that use the same hashtags each year but leave it dormant the rest of the time:

over time, as tags are used less frequently, other people can reuse them — no domain squatting!

The hashtag debate

Although we all accept hashtags as a normal part of Twitter now (whether we like it or not), not everyone was keen to jump on board the hashtag train originally. Chris had to fight for his hashtag plan and convince others of the benefits. In a post on his blog, Chris wrote this:

Some people just don’t like how they look. Still others feel that they encumber a simple communication system that should do one thing and one thing well, secondary uses be damned if they don’t blend with the how the system is generally used.

More recently, he told GigaOM:

In the beginning people really hated them! People didn’t understand why we needed hashtags, and the biggest complaint was that people just didn’t like how they looked.

We often think of hashtags as being integral parts of tweets, Chris intended them to act as meta data for a tweet. That is, something to provide extra information about a tweet, like where you are or what event you’re referring to.

Every time someone uses a channel tag to mark a status, not only do we know something specific about that status, but others can eavesdrop on the context of it and then join in the channel and contribute as well… And, perhaps best of all, anyone can choose to leave or remove topics that don’t interest them.

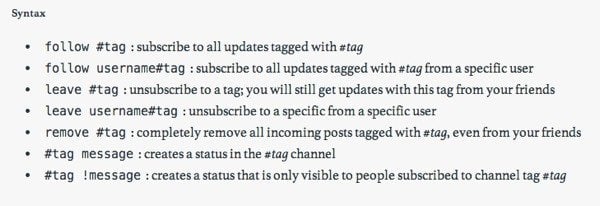

Since Twitter was in such an early stage at this point, users actually had to choose to follow a specific hashtag to receive all the tweets that included it. after which, a hashtag could be unfollowed (i.e. removed).

Here’s the proposed syntax from Chris himself:

Nowadays we obviously see hashtags pass by in our timelines or find them via Twitter’s search feature, and only choose to join in a hashtag conversation by clicking on a particular hashtag to view the other tweets or including the tag in our own tweets. It’s a far cry from Chris’s original, simple idea, but then Twitter itself has developed hugely since then.

Although Twitter has since become known as a platform that lets its users create features, (when Chris proposed hashtags, early users had already had a hand in developing @replies and direct messages), the Twitter team weren’t keen on Chris’s idea. Co-founder Evan Williams told Chris that hashtags were too nerdy to go mainstream, so Chris was left to encourage their adoption on his own.

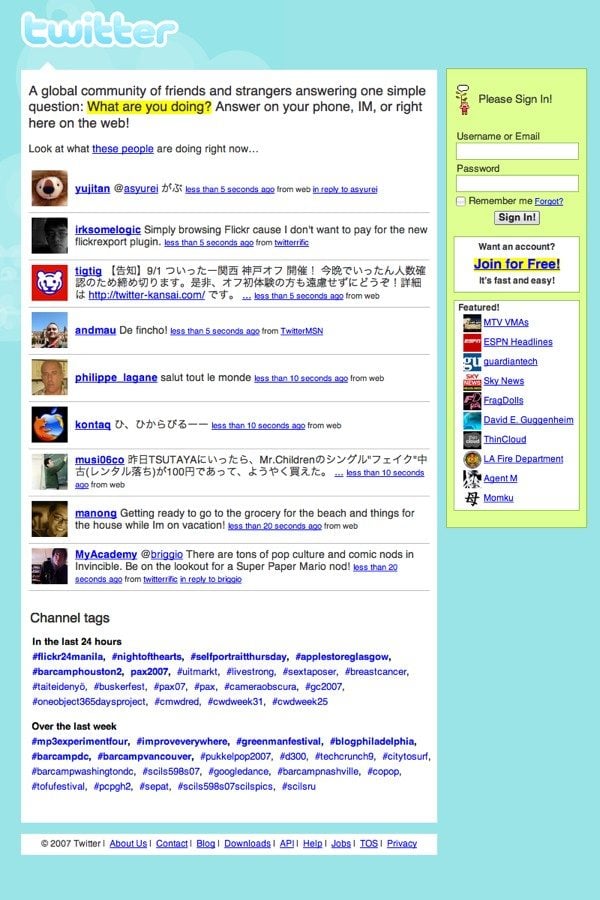

This is one of the mock-ups Chris created to show the Twitter team how hashtags could work:

This was nothing new, though. When users first started referring to Twitter posts as “tweets,” the founders weren’t impressed, and tried to stave off adoption of the term. It took widespread user adoption of this jargon and features like hashtags for the company to come around.

Now, it seems, Williams is confident that the company made the right move by listening to users:

Most companies or services on the Web start with wrong assumptions about what they are and what they’re for. Twitter struck an interesting balance of flexibility and malleability that allowed users to invent uses for it that weren’t anticipated.

Messina is especially proud of inventing hashtags in retrospect “because they’re a hack and they prove that simple solutions are often the best ways to solve a problem, rather than waiting for a technology solution.”

Getting the most out of Twitter hashtags

Although hashtags have evolved with the development of Twitter itself, we can gain some useful insights by looking at Chris’s original plans for the hashtag, and how it could be useful.

Adding context

For shortened URLs or ambiguous tweets, adding a hashtag can immediately provide context for other users, without affecting the content of the tweet itself (supposing we look at hashtags how Chris proposed them—as meta-data).

Joining a conversation

If your post is about a topic, but doesn’t reference it specifically, users who monitor that particular topic’s keyword or common hashtags may miss your tweet. Adding a hashtag to the end of your post can slot your tweet into those streams so it doesn’t get missed. I often do this when tweeting about startups, since the word “startups” doesn’t often fit naturally into the body of my tweet.

How We Increased Our Conversion Rate By 311% http://t.co/CjBLSH0JIw #startups

— Belle (@BelleBethCooper) July 28, 2013

Collecting tweets about a trending topic

As in the case of the San Diego Fires, using one hashtag across all users who contribute tweets about a particular topic can help other Twitter users to keep up. Regardless of who you’re following, if you follow a hashtag, particular for a current event like a sports match or an election, you can see all of the tweets about that topic in one place.

In fact, it was a similar situation to the San Diego Fires that led Chris to the idea of hashtags to begin with. When he noticed people tweeting about earthquakes in the Bay Area, he started looking for a better way to coordinate these communications via Twitter.

Avoiding going overboard

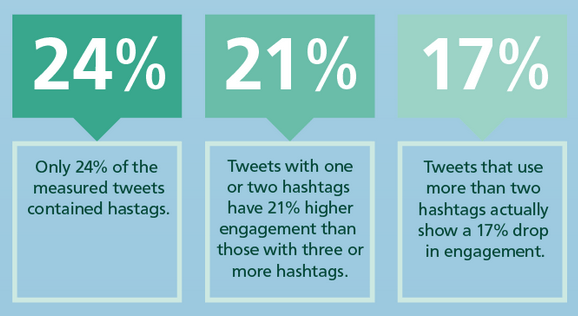

I’ve mentioned social media stats and especially Twitter stats before that show using more than two hashtags can diminish your changes of engagement on a tweet:

It turns out Chris isn’t a fan of over-hashtagging either.

Already it’s been made clear to me that the use of hashtags can be annoying, adding more noise than value.

While he originally suggested that hashtags could be added within a tweet for emphasis, he later decided that approach was “gratuitous” and that “removing the hashes doens’t actually reduce the meaning” but leaving them out can make a tweet look much better. Here’s the example he offered:

With hashes:

“Eating #popcorn at #Batman in #IMAX.”

Without hashes:

“Eating popcorn at Batman in IMAX.”

The lesson here being think carefully about using hashtags—why are you using that hashtag? Will other users gain value from it? Or is it just cluttering up your tweet and making it harder to read?

Overall, I think the best advice we can take away for using hashtags comes directly from Chris himself:

Used sparingly, respectfully and in appropriate measure, I think that the value generated from the use of hashtags is substantial enough to warrant their continued use.

What could be next after the Hashtag: Slashtags and more

Chris hasn’t been twiddling his thumbs ever since hashtags were officially adopted at Twitter. In fact, he’s gone ahead and invented some new tweet conventions, though they haven’t had quite the successful adoption that hashtags did.

Later coined “slashtags,” these are more ways to add useful meta-data to tweets in a consistent way, according to Chris.

By using a slash: “/” at the end of his tweets, Chris points out where meta-data begins and the tweet’s content ends. Considering Twitter’s original billing as a micro-blogging platform, it actually makes sense to include meta-data if you can squeeze it into 140 characters.

Chris has three new “pointers,” or meta-data terms he uses after the slash:

- via to indicate where an idea came from (as opposed to a RT, when the entire tweet is forwarded on, rather than the idea in your own words)

- cc to ensure a particular person sees a tweet, without directing it only to them with an @reply

- by to give credit for a quote, for instance.

Chris set out rules for how these can be used by any Twitter users in the hopes that they might see wider adoption and create a more consistent, readable Twitter stream that encapsulates necessary meta-data as well as tweet content.

3 more ideas to perfect the hashtag further

As I was researching this post, I read several blog posts by Chris and other Twitter users from around the time hashtags were first seeing more adoption across Twitter. I found it really interesting to look at everyone’s feature wishlists and predictions for how hashtags might evolve in the future and wanted to share some to finish off this post.

Whisper circles

Chris himself briefly suggested the idea of a “whisper cirlce” or “inner circle” that would function similar to a private Facebook group or Google+ circle, letting you send tweets to a small number of users, while still having the option to post publicly to your standard timeline. He even suggested being able to post tweets that only you could see, if you wanted to.

Formatting multi-word hashtags

In this post by Stephanie Booth, she describes some possible ways to format multi-word hashtags so they are easier to read.

One suggestion was to use a plus symbol in-between words, like so: #san+francisco. Since Twitter’s “track” feature at the time (sort of like a saved search that got sent to your phone) didn’t index plus symbols properly, if you tracked the phrase “san francicso,” you wouldn’t see these particular tweets.

Another one I really liked was to use opening and closing hashes, like parentheses: #san francisco#. Obviously, that one never took off, either.

Hashtags from your followers

I’m sad this one hasn’t been implemented, because it sounds pretty useful. It’s another suggestion from Stephanie’s blog post, that would help with hashtag overload, especially at big events or during big news breaks:

Once “everybody” starts using hashtags, it will be very useful to be able to narrow down a collection of tagged tweets to “my followees only”; imagine I’m at LeWeb3, and everybody is twittering about it: I’m not interested in getting the thousands of tweets, just those from the people I’m following

So that’s it—a concise, but hopefully well-rounded history of Twitter’s hashtag. There were more than a few surprises in there for me—what surprised you the most? Let us know in the comments.

Image credits: Chris Messina 1, 2 and 3

P.S. If you liked that post, you might also like A scientific guide to posting Tweets, Facebook posts, Emails and Blog posts at the best time and 10 Surprising New Twitter Stats to Help You Reach More Followers

Try Buffer for free

190,000+ creators, small businesses, and marketers use Buffer to grow their audiences every month.