January 3, 2011, was my first day at Buffer as sort of the social media intern.

The introductory task that Joel and I came up with was fairly simple: Spend 30 minutes a day on Buffer’s Twitter account and help it grow. We had about 78 followers at the time, and the 100 follower mark was in sight.

I had just turned 20 years old, was halfway through my second year in college and I was ready—for anything really. It didn’t matter what, I just wanted to go and do.

So I did. I made a lot of mistakes and big messes to begin with. I started auto-DM’ing people on Twitter to push Buffer onto them like a used car salesman. I’m still cringing now thinking about that. But also some good things! I discovered that simply interacting with people and giving great customer service goes a long way.

From Twitter, I discovered blogs and blog comments in particular. I started to make friends with every single person who wrote anything remotely resembling the topic of social media and marketing.

Joel had given me a copy of How to Win Friends and Influence People, and I was so hooked. No more sleazy tactics—just making friends, being there for people with questions, and producing valuable content and insights. It was so fun!

From intern to maker to manager

From there I discovered that I could in fact, write articles myself. So I did—very poorly at first, and gradually better. Here’s an example of one of my earlier posts. Over time, I churned out hundreds of posts and roughly worked from 8 a.m. to 8 p.m. every day, topped off with a daily sync with Joel at 8 p.m. to go over open questions from the day. I remember falling into bed so tired and exhausted, but also so fulfilled, that I’d jump straight out of bed the next morning to do it all over again. Commenting, writing blogposts, answering questions on Twitter, syncing with Joel. Rinse and repeat.

Gradually, my role at Buffer changed and evolved and I learned about more things. How to get press coverage, how to raise money, how to hire people, how to do more marketing things, how to do business development and partnerships, how to have sales calls, how to do public speaking, how to do parts of product development and so much more. I even mixed in learning some Ruby on Rails and Javascript in there.

I loved and still love learning about all those things. It was all doing. For the first 2-3 years, I was 100% doing things.

As we started to bring more people on board, it was mostly on the product and customer service side, so I kept cranking things out—bigger projects, bigger partnerships, bigger PR outlets. That’s how I kept learning; by setting goals for myself, like “OK, we made TechCrunch, now let’s get into the New York Times.”

After another year, I hit a ceiling. I’m pretty sure I could still get a lot better on all those fronts; I was doing so many things simultaneously that I never truly became an expert at any of them. Yet I began to get less satisfaction out of writing that next blog post, even if it blew up to hundreds of thousands of readers and brought in lots of new customers.

That was lucky, because slowly but surely the team had grown more and more, even on the marketing side. Suddenly I was in a position to do other things. That’s when it dawned on me that it might not be about doing more, but about helping others do more. It was time to start a new journey to understand management.

At first, I thought I’d just pick up management in the same way that I picked up other skills, like PR or customer development.

Now, about 2 years in, I’m realizing that being a manager isn’t just another skill. It’s about changing at a much more fundamental level.

Doing vs. managing: They’re opposites in many ways

The first thing I noticed is that “doing” and “managing” are almost polar opposites. When I was doing, I was producing the work and needed lots of heads-down time to make things. As a manager, I’m producing almost nothing. The best thing I can do is help others who are doing all the producing.

Yet all my life, I’ve been so wired to “do.” From the day I wanted to play pro soccer at age 6, it was all about doing—putting in the work, training and showing up. Over and over again, like the blog posts later on at Buffer.

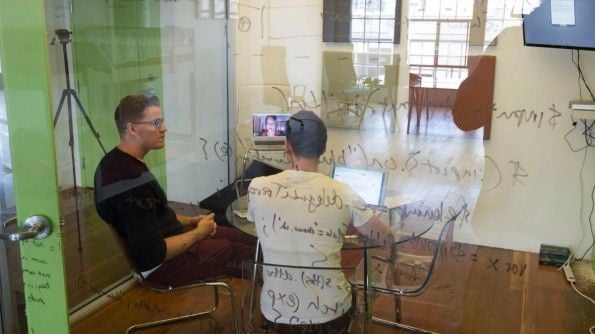

I had to unlearn that forward motion of doing. Literally. When I’m in one-on-one mentoring sessions today, the first thing I make sure to do is lean back physically in my chair.

It’s a signal to myself that I’m not here to do. I’m here to listen. The other person just had a full week of doing, so there are lots of challenges and achievements that came out of that. They’ve had enough doing; they don’t need me to jump in for another load of it.

It reminds me a lot of meditation, where you first notice how many thoughts you have when you’re sitting still. Slowly, gradually your thoughts become less. It happens all on its own by having that space and by me leaning back and letting go. In a way, being a manager is one big meditation exercise—noticing my “doing” habits and gently avoiding acting on them.

I’m not here to do. I’m here to listen.

Empathy and listening have a whole new meaning for me since becoming more of a manager.

To really listen is really hard. To stay with someone’s thoughts as they take you through a challenge or opinion and not stopping them 10 seconds in with “Let me stop you there and give you the solution” is so hard. The habit of doing is so strong and ingrained that I want to pounce at every opportunity.

When I don’t do a good job of “leaning back,” here’s a look at what’s going on in my brain when I’m in a one-on-one with someone:

“Oh interesting! Yes, I see, a problem with this project. Yes, hmm, he/she should do this, then say this to their team. They should also read this article, it’s a good article about management and giving feedback. Hmm, generally everyone on the team should maybe read this article. Maybe after this I should share it with the team on Slack. Or on Twitter, I should maybe add it to my Buffer. I haven’t been filling up my Buffer in a while, so I should do that a lot more. I think this’ll get a lot of engagement on Twitter.”

And I’m off on this train of thought, missing most of what the person said. To top it off, I jump in with my advice that I concluded about 10 seconds in.

Try this quick listening exercise for yourself

Try this for yourself: Ask someone a question or have someone tell you a story and to just sit there and listen. Notice how your thoughts wander off to what you’ll have for lunch later, or what you want to add to the conversation yourself. Notice how you get distracted by what else is going on, or someone else walking past. Bring it back to the person you’re listening to every time, take in every word like it’s the first spoken word you’ve heard.

This is so hard, but so rewarding. I started noticing so much more when I began this practice. How is someone saying it, really? Their hand movements, their body language, their tone. For me, this isn’t a form of examination and scrutiny but really a way of true listening and wanting to understand what they’re trying to put across.

Practicing just listening is probably the most worthwhile thing I’ve learned to do as a manager. Of course, there’re so many other things to being a manager—organizing, setting up of meetings, following up, making tough decisions about projects and people, holding people accountable, managing projects and more. But the biggest reward and challenge is in really listening and learning how to ask great questions.

Asking better questions: True curiosity is key

Asking great questions is hard, too. For a long time I’ve asked questions very poorly—I still do, to a large degree, but I’ve picked up on a few things. I think this is all connected to the “doing” again—creating a habit of asking more questions instead of wanting to provide an answer after listening is all part of the rewiring process.

I’ve learned that any question I ask where I expect a specific answer isn’t a very good question. Questions that start with “Would you” or “Do you” aren’t good questions, because I’m already assuming a very narrow set of possibilities.

The good questions tend to be a bit more open-ended and might start with “How” or “Why.” Even those are hard—sometimes I ask those questions with pure curiosity, but sometimes I disguise a “would you” question in there. Tricky stuff!

But I’ve gotten better. I’ve learned that I don’t need to know all the answers—in fact, it’s much better if I don’t. The more questions I ask, the more likely the other person is to come up with the answer themselves.

Finding happiness as the coach instead of the player

Sometimes going from lots of doing, writing and producing to listening and asking questions feels like bringing a car to a stop from 100 miles an hour. I’m often particularly glad about working remotely, especially when I notice myself leaning forward and then back, forward and backward again.It would look quite funny in an office!

I’ve learned that being a manager is a mindset shift. You’re no longer a player, you’re the coach. You can’t score the winning goal anymore, no matter how hard you try.

And I still try sometimes. I’ve tried to direct someone step-by-step to score the winning goal from the sidelines. It doesn’t work. The best way coaches can help is by listening, asking questions and only then making suggestions.

Our friends at HelpScout actually refer to managers and individual contributors as coaches and players, respectively. The reasons why were very interesting to me:

“These words reinforce important associations for us culturally. First, when you think of professional sports, players come first. Fans wear player jerseys for a reason. Players … embody what we want to be about. A coach’s role is to serve players, to help them seek excellence, and to ensure their team is greater than the sum of its parts.”

To help players seek excellence, I believe coaches need to see it from their viewpoint and share advice that’s right for their situation and motivation. Not the old “This is what I have done that worked, so you should do it, too.” Listening and then asking good questions is maybe the only way to get there.

After 5 years at Buffer, this transition from maker to manager is the toughest—and most rewarding—thing I’ve worked through so far. It’s taken about 2 years and I still feel very early in the journey. Slowly, as I’ve uncovered more blind spots and opportunities, I’ve begun to see the full picture emerge of where I want to go to be a really good manager. That’s maybe the most satisfying part, that I can now see the light—no matter how far away it may seem sometimes.

I’d love to hear your thoughts on this. Do you gravitate toward the mindset of a maker or a manager, or some combination of the two? How do you practice skills like deeply listening and asking great questions? I’m keen to get your insights, tips and feedback in the comments!

Try Buffer for free

190,000+ creators, small businesses, and marketers use Buffer to grow their audiences every month.